From Teaching to Technology

Teachers have many skills that make them excellent candidates for the tech workplace. Decision-making, adaptability, management, and problem-solving are skills that good teachers and programmers have in abundance.

Like many educators during the Covid-19 pandemic, Kat Wegrzynowicz, a military spouse and former special education instructor, left teaching. She decided to pursue a new opportunity in a tech career and started Code Platoon’s Immersive Full-stack Software Engineering Bootcamp three years after her husband, Greg Wegrzynowicz, graduated from the same program.

Kat was a special education teacher and case manager for eight years. In 2014, she met Greg, three years after he retired from the Marine Corps. They got married in 2019, the same year he graduated from Code Platoon.

Then, the Covid-19 pandemic struck.

“My teaching career felt out of control due to Covid,” Kat said. “So I left teaching full-time and worked that school year remotely as a contractor.”

With more free time on her hands, Kat explored her interest in coding. She taught herself JavaScript fundamentals and did some peer programming on Zoom with a friend of her husband.

“I had some great experiences but needed to strengthen my knowledge to be more competitive on the job market,” Kat said. “Once I got to that point where I needed structure, I thought of Code Platoon. I knew they had a great program based on Greg’s experience.”

As a military spouse, Kat’s benefits options were limited. Military spouses don’t qualify for VA benefits like VET TEC, and Kat’s husband already used his GI Bill. But, when Kat was accepted, she qualified for one of Code Platoon’s military spouse-eligible scholarships. She received the full-tuition Women in Technology scholarship.

“I was nervous at first to pursue software engineering and attend Code Platoon,” Kat said. “Being in education, I was used to working with mostly women. I’d also heard that other bootcamps are very competitive, with students that feel threatened by each other’s success. But at Code Platoon, the staff, instructors, and students have all been supportive and inclusive.

“Emma (the Diversity and Inclusion workshop leader) showed my class some challenges women in technology face. She gave the women students the idea to be more mindful about connecting with other women in coding. We started a Slack group to network and help each other out.”

After graduating in May, Kat will seek positions at inclusive companies that offer learning opportunities for her first tech job. She has no preference for remote or in-person work if the company has a good workplace culture and a supportive environment for junior developers.

“I encourage anyone interested in coding to consider Code Platoon. Their program offers a lot of advantages.

“When I left teaching, I didn’t think there was a place for me in technology. But Code Platoon showed me that tech has a place for anyone who can dedicate themselves to it.”

Are you a military spouse interested in attending Code Platoon? View our scholarship options for military spouses and apply to Code Platoon today.

Kayla Elkin is the Marketing Content Specialist at Code Platoon. In this role, she utilizes her marketing, writing, and editing skills developed from previous positions in higher education and educational technology. Kayla has degrees in English and Sociology from Clemson University and completed the Study in India Program (SIP) at the University of Hyderabad. She lives with her partner in northern Chicago.

Michael, a former Infantry Sergeant, joined Code Platoon in 2020. After graduation, he apprenticed with

Michael, a former Infantry Sergeant, joined Code Platoon in 2020. After graduation, he apprenticed with  “Code Platoon’s focus on getting us a job at the end of the program is phenomenal,” Seth said. “You start with career prep, and by the end, you have the chance to interview with companies spanning the financial sector to consulting. Code Platoon chooses its partners carefully and sets students up for success.

“Code Platoon’s focus on getting us a job at the end of the program is phenomenal,” Seth said. “You start with career prep, and by the end, you have the chance to interview with companies spanning the financial sector to consulting. Code Platoon chooses its partners carefully and sets students up for success.

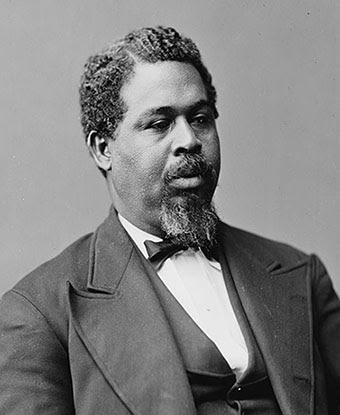

enough money, Smalls joined the Confederate Navy and developed enough trust with his commanders that he was allowed to pilot a ship which he then craftily sailed away in – with eight other enslaved people – to freedom in the North.

enough money, Smalls joined the Confederate Navy and developed enough trust with his commanders that he was allowed to pilot a ship which he then craftily sailed away in – with eight other enslaved people – to freedom in the North. By 1964, Clara became an instructor at Fort Sam Houston, where she taught until 1967, which means that many medics who went to Vietnam received education from her. In 1967, she earned her master’s degree in medical-surgical nursing, moving on to teach and work at Walter Reed Medical Center.

By 1964, Clara became an instructor at Fort Sam Houston, where she taught until 1967, which means that many medics who went to Vietnam received education from her. In 1967, she earned her master’s degree in medical-surgical nursing, moving on to teach and work at Walter Reed Medical Center. In October of 1944, Lt. Thomas arrived on Normandy Beach, and by November, they had connected with Patton’s Third Army, seeing their first combat by the end of that month. However, it was the middle of December when his unit found itself in a position that led Thomas to take actions that would eventually earn him the Medal of Honor.

In October of 1944, Lt. Thomas arrived on Normandy Beach, and by November, they had connected with Patton’s Third Army, seeing their first combat by the end of that month. However, it was the middle of December when his unit found itself in a position that led Thomas to take actions that would eventually earn him the Medal of Honor.